Author Shailendra Bahadur Thapa

SATV 8 April, Kathmandu: Traditionally, the first "Defense and Trade Transit Treaty" between Nepal and Tibet (China) was signed in 630 AD during the reign of King Tsrong Tsang Gampo of Tibet. This treaty granted Nepal the right to trade and transit with Tibet (China). As a result, goods such as salt, wool, and gold would come from Tibet (China) to Nepal, while Buddhist statues, handicrafts, and other items would go from Nepal to Tibet (China).

However, later in 1911 AD (B.S. 1968) and 1949 AD (B.S. 2006), due to modern political changes in allied China, the 1950 AD (B.S. 2007) treaty between Nepal and India, and the political transformation in Nepal in 1951 AD (B.S. 2007), Nepal's balance with China declined while its dependence on India increased. Consequently, Nepal's trade and transit rights began shifting towards India.

Nevertheless, Article 278 of the Versailles Treaty and the 1921 Barcelona Convention recognized the right to freedom of transit and incorporated it into international law. The 1958 Geneva Convention on the Law of the Sea was the first to codify the transit rights of landlocked countries under Article 3.

Almost a decade later, on May 26, 1967, the Arniko (Kodari) Highway was officially inaugurated. This event is diplomatically regarded as establishing Nepal's "second degree of freedom" with China, balancing its "first degree of freedom" with India, thereby laying the foundation for Nepal's dual transit rights. This ensured equal degrees of freedom for Nepal.

Generally, the transportation of consumable goods from one country to another, or the import/export activities conducted through a third country, is known as transit. The issue of transit routes is a major challenge for landlocked countries like Nepal and Bhutan.

To address this challenge, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) 1982 granted landlocked nations the right of access to the sea for transit purposes. It also ensured their proportional right to utilize maritime resources.

Nearly 34 years after UNCLOS 1982, Nepal signed a Transit and Transport Agreement with China on March 21, 2016, establishing dual transit rights while maintaining balance with India. To implement this agreement, Nepal and China signed a bilateral transit protocol on April 29, 2019.

Following this, Nepal has gained policy-level access to four Chinese seaports—Tianjin, Shenzhen, Lianyungang, and Zhanjiang—and three dry ports—Lanzhou, Lhasa, and Shigatse.

Recent Nepal-China strategic cooperation treaties and agreements hold significant meaning, signaling expanding global partnerships and fostering Asian unity.

Historically, Nepal has maintained independent diplomatic relations, sometimes aligning more closely with China and at other times with India, to secure its landlocked rights. This relationship is based on Nepal’s balanced diplomacy and the principle of peaceful coexistence.

The problems faced by landlocked countries in Asia vary significantly due to their unique geopolitical situations. Countries without direct sea access have traditionally relied on neighboring coastal nations' ports to engage in international trade.

While air transport is an alternative for global trade, it is often too expensive for bulk shipments, making it inefficient for large-scale commerce. As a result, maritime transport remains the most cost-effective and widely accessible method for international trade.

To overcome their geographical limitations, landlocked countries have historically entered transit agreements with coastal states to gain access to seaports. A landlocked country is defined as one that must pass through another nation’s territory to reach international waters.

Given these challenges, there is a pressing need for an international theoretical discourse based on the "1+8 Concept" to promote landlocked rights in a manner that aligns with Asia’s distinct geopolitical realities.

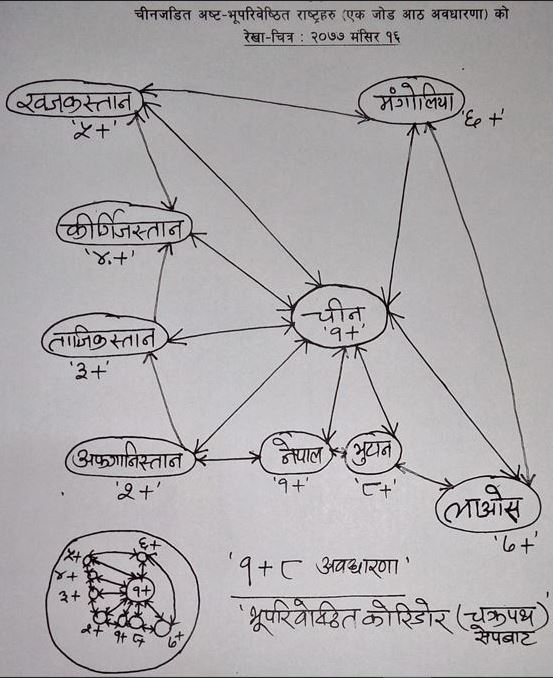

Concept of the "Eight Landlocked Circuit" (1+8 Concept)

The "Eight Landlocked Circuit" (Ashta-Bhupariveshit Paripath), also known as the "1+8 Framework," is a groundbreaking geopolitical concept formally registered in Nepal on December 1, 2020, under Registration No. 5033 at the Office of the Prime Minister and Council of Ministers. This framework addresses the unique challenges faced by landlocked nations, particularly the 12 Asian countries among the world’s 48 landlocked states, of which eight—Afghanistan, Bhutan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Mongolia, Nepal, and Tajikistan—share a direct border with China. The core idea revolves around leveraging China’s strategic position as a maritime hub to secure collective transit rights for these eight nations, enabling them to access global trade routes more efficiently. By forming a unified bloc, these countries can negotiate better terms for using Chinese seaports (e.g., Tianjin, Shenzhen) and dry ports (e.g., Lanzhou, Lhasa), reducing their historical dependency on single transit corridors (e.g., Nepal’s reliance on Indian ports).

The concept goes beyond mere logistics, targeting the psychological and policy barriers of landlocked nations—often termed "landlocked mentality"—by promoting long-term strategic planning, sustainable development, and economic diversification. While China serves as the central maritime gateway (the "1"), the eight nations (the "8") collaborate to strengthen their bargaining power. Leadership in this initiative could be spearheaded by China and Nepal (the proposal’s originator), though the framework remains open to debate, refinement, and global input. Notably, the model aligns with existing international laws like the UNCLOS 1982, which guarantees landlocked states’ transit rights, but requires further legal and diplomatic formalization.

However, challenges persist, including balancing relations with neighboring powers like India (which borders Nepal and Bhutan) and securing multilateral agreements. If successfully implemented, the 1+8 Framework could revolutionize trade dynamics in Asia, offering landlocked nations greater economic autonomy while reinforcing China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Beyond immediate benefits, it sets a precedent for global landlocked regions, fostering regional cooperation, infrastructure development, and equitable growth. The concept remains a flexible, evolving strategy, inviting constructive criticism and collaborative innovation to realize its full potential.

The Octo-Landlocked Circuit (1+8 Framework) is a forward-thinking concept designed to foster collective prosperity, shared transit rights, and collaboration among landlocked nations. It is not intended as a political challenge to any nation or as a strategic threat, but rather as a psychological and developmental approach based on friendship, peaceful coexistence, and constructive collaboration. This vision aims to reshape Asia's geopolitical landscape by promoting unity rather than division, focusing on shared benefits and mutual growth.

Core Philosophy and Structure

China as the Central Hub (1+):

At the heart of the Octo-Landlocked Circuit is China, positioned as the central maritime hub for eight landlocked nations. These countries, which share borders with China, include:

Nepal (Kathmandu)

Afghanistan (Kabul)

Tajikistan (Dushanbe)

Kyrgyzstan (Bishkek)

Kazakhstan (Astana)

Mongolia (Ulaanbaatar)

Laos (Vientiane)

Bhutan (Thimphu)

These eight nations form a geopolitical circuit, negotiating shared transit access, trade facilitation, and infrastructure development, with China acting as the key partner in enabling these exchanges.

Synergy with China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI):

The 1+8 Framework is closely aligned with China’s "One Belt, One Road" (OBOR) and "Regional and Pathway" initiatives. It serves as a catalyst for regional integration, complementing these larger projects and emphasizing collaborative development rather than positioning itself as a rival to existing blocs. The framework is grounded in the principles of the United Nations, international law, and the rights of landlocked states as outlined in UNCLOS 1982.

Strategic Objectives

Economic Liberation: The 1+8 Framework aims to reduce dependency on single transit corridors, such as Nepal’s reliance on India, by diversifying access to Chinese ports like Tianjin and Shenzhen, as well as dry ports like Lanzhou and Lhasa.

Psychological Shift: The concept also seeks to address the "landlocked mentality," encouraging self-reliance and regional cooperation through a collective approach.

Observer Roles: Coastal nations, including India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Japan, are invited to participate as observers in the initiative. This ensures transparency and secures regional buy-in without antagonizing any major power.

Case Study: Nepal’s Dual Advantage

Nepal stands as a key example of the framework's potential. Positioned between China and India, Nepal benefits from a balanced relationship with both, while advocating for tri-lateral cooperation. Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness (GNH) model offers valuable lessons for sustainable development that could be adapted by Nepal and other nations within the circuit.

Challenges and Global Implications

Diplomatic Balance: One of the key challenges of the 1+8 Framework is managing the delicate balance between China and India, particularly in light of their rivalry. The concept emphasizes "tri-lateralism" rather than exclusion, promoting collaboration over competition.

Implementation: To succeed, the framework requires legal treaties, infrastructure investments, and multilateral consensus. The commitment of all involved parties is crucial for effective execution.

Global Implications: While the framework is focused on Asia, it holds broader significance for landlocked nations in other regions, including Africa and Europe, who may seek similar coalitions.

The Nepali Dream: A Blueprint for Asian Unity

This concept, which originated in Nepal, has the potential to unite landlocked nations across the continent and beyond. Its goals include:

Resolving transit inequalities by sharing sovereignty over key trade routes.

Promoting "Asian solidarity" without antagonizing global powers.

Advancing world peace through cooperation and collaboration, demonstrating that collective progress is more powerful than isolation.

Conclusion: From Theory to Action

The 1+8 Framework is not just an abstract ideal, but a practical roadmap for the future. Its success depends on:

Leadership: Joint stewardship by China and Nepal, ensuring shared responsibility and vision.

Inclusivity: Engaging coastal nations as observers to build trust and cooperation.

Adaptability: Learning from successful models, such as Bhutan’s GNH and Kazakhstan’s Caspian connectivity.

By aligning self-interest with collective progress, this concept has the potential to redefine the geopolitical landscape of the 21st century, transforming landlocked nations from peripheral players into pivotal partners.

(The author is a doctoral researcher in Nepal-China political and economic relations.)