The edible oil industry in Bangladesh has seen massive change over the past two decades on the back of the consumption of the key cooking ingredient in line with the country's growing population and increasing purchasing power.

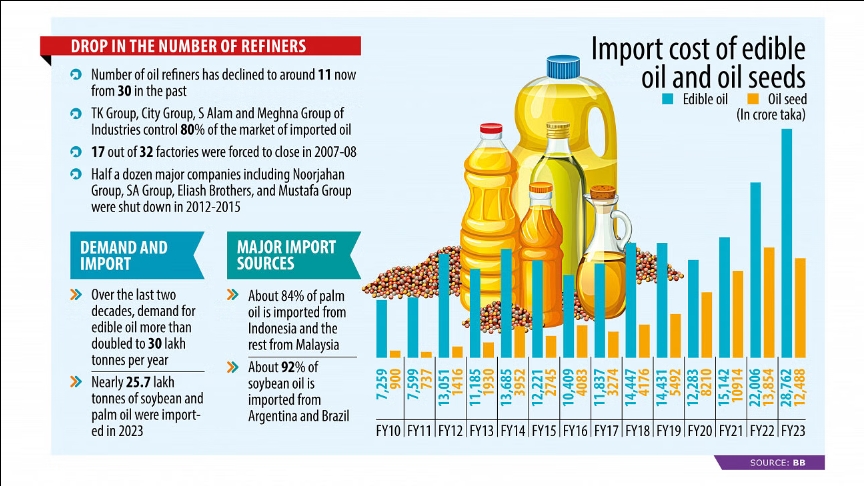

However, the number of refiners has declined by a third during the period as many could not sustain their business, leaving just 11 companies to currently operate in the edible oil market.

"As a result, the market has turned oligopolistic in nature and major players can influence prices in a way that affects consumer interests," said Ghulam Rahman, president of the Consumers Association of Bangladesh (CAB).

Among the 11 companies, TK Group, City Group, S Alam Group and Meghna Group control a majority of the imported edible oil market.

Data from the National Board of Revenue (NBR) shows that nearly 25.7 lakh tonnes of soybean and palm oil were imported in 2023, with the four companies accounting for 80 percent of the total amount.

The four companies collectively catered to about a fourth of the demand for edible oil just 10 years ago, meaning their collective market share has tripled since then.

So why did such a change take place?

The foremost reason is price instability in the global commodities market, on which Bangladesh relies heavily to meet its requirements.

"Many failed to sustain their edible oil business as they suffered losses amid price volatility in the international market," said Golam Mawla, a trader at Moulvibazar in Dhaka, one the country's largest wholesale kitchen markets.

However, this alone does not tell the whole story.

"A section of businesspeople had taken bank loans to buy land and set up oil refining facilities expecting high returns," said AKM Fakhrul Alam, a former regional manager of the Malaysian Palm Oil Council.

"But they did not get that [profit] and rather suffered losses," he added, while informing that unhealthy competition among market players also drove a number of them out of business.

The annual requirement for edible oil in Bangladesh more than doubled to 30 lakh tonnes over the past two decades. But still, many importers and traders suffered heavy losses over the years due to price volatility in the international market, particularly in 2008 and 2012, market players say.

Businesses in Chattogram, a vital region for the edible oil trade given its access to port facilities, said the trouble began when the caretaker government forced them to sell the product for less than its import cost in 2007-08. As a result, 17 of the 32 local edible oil processors were forced to shut down.

The industry saw another significant setback between 2012 and 2015 when more than half a dozen of the major edible oil processors, including Noorjahan Group, SA Group, Eliash Brothers, and Mustafa Group were closed.

Abul Hashem, an edible oil wholesaler at Moulvibazar, said the industry requires huge capital and entails a lot of risk.

"So, a good number of small entrepreneurs closed down their edible oil business between 2008 and 2010 for failing to absorb huge losses."

Later, loan default and aggressive business practices forced couple more of the businesses to close down, Hashem said.

Traders said some importers were engaged in aggressive trade practices and bought land and invested in unproductive sectors without paying back bank loans, and these ultimately brought them down.

As a result, TK Group, Meghna Group, City Group, and S Alam Group remain the major players in the edible oil market, which is highly dependent on imports from Southeast Asia and Latin America.

These conglomerates consolidated their positions and cemented their foothold by capitalising on the sudden exit of other industry giants.

Industry insiders say that although several new companies, including Bashundhara Multi Food Products, Smile Food Products, Sena Edible Oil Industries and Delta Agro Food Industries, entered the market between 2016 and 2022, they are yet to make any significant impact.

Mohammad Abul Kalam, managing director of TK Group, denied allegations that they make excessive profit as only a few companies control the country's market.

"There is no opportunity for excessive profit. Various government agencies keep the market under surveillance at all times."

He opined that many big companies even disappeared from the market due to government policies.

"We buy oil from the open market, where there is one price in the morning and another in the afternoon. But at various times, the government forced us to sell products at fixed prices. So, many institutions were lost for this policy."

Kalam suggested that prices should not be controlled by the government and instead left to the market system.

Bangladesh is not the lone market where a few companies control the cooking oil industry.

For example, India's edible oil market is dominated by the presence of old conglomerates such as Adani Willmar, Patanjali Foods, and Agro Tech Foods, according to German data service provider Statista.

In Pakistan, 75 percent of the market is controlled by 11 major brands.

CAB President Rahman said consumers could also benefit in an oligopolistic market if all the firms try to increase their market share.

"But consumers' interest gets affected if there is an understanding among the firms. Here, the regulatory role to ensure competition is vital."